For several years, municipalities in Massachusetts have been cracking down on begging. Friday afternoon marked the beginning of the end of these crackdowns. In a powerful and unequivocal decision, a federal judge ruled in McLaughlin v. City of Lowell that an anti-begging ordinance in Lowell is completely contrary to the freedom of speech protected by the First Amendment.

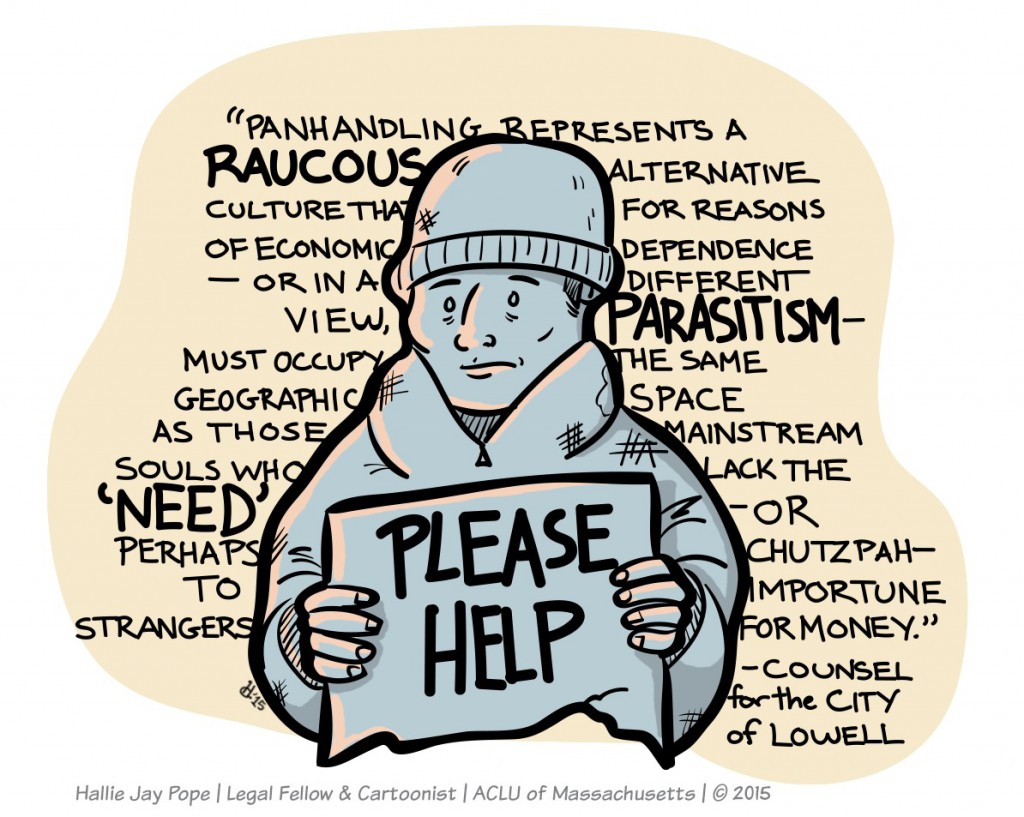

Lowell is one of two Massachusetts cities—the other is Worcester—defending anti-begging ordinances against court challenges by the ACLU of Massachusetts and the law firm Goodwin Procter. The Lowell ordinance has two parts: one that bans panhandling in Lowell’s 400-acre downtown historic district, and one that bans supposedly “aggressive” panhandling. Lowell defended these bans with, among other arguments, the remarkable suggestion that begging attracts “modern-day court jesters or buffoons,” and that it represents a “raucous alternative culture” rather than any ideas worthy of the First Amendment:

“[P]anhandling represents a raucous alternative culture that for reasons of economic dependence—or in a different view, parasitism—must occupy the same geographic space as those mainstream souls who lack the ‘need’—or perhaps the chutzpah—to importune strangers for money.”

Lowell’s argument was thoroughly rebutted by the ruling issued Friday afternoon.

Citing several cases, including the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court’s landmark decision in Benefit v. City of Cambridge (an ACLU of Massachusetts case), U.S. District Judge Douglas Woodlock wrote that begging is “an expressive act” because it conveys a message of need. As a result, laws that restrict begging but not other speech amount to content-based censorship, which is presumptively unconstitutional. Indeed, Judge Woodlock explained that even Lowell’s ban on “aggressive” begging is problematic because it punishes aggressive conduct by beggars more harshly than it punishes aggressive conduct by other people.

Worse yet, Lowell’s aggressive begging was in many respects a marketing campaign. Judge Woodlock noted that the ordinance created 20-foot buffer zones around various objects—such as a transit stop, a theater, or a bank—within which all panhandling is deemed “aggressive” even if someone is just “sitting and holding a sign asking for donations.”

In a kind of judicial jiu-jitsu, Judge Woodlock also pointed out Lowell’s defense of its ordinance was undone by its own argument that panhandling is an “alternative culture.” He wrote that “the City’s fervent denunciation of the culture of panhandling also evidences” that Lowell had a “content-based intent in enacting the Ordinance.”

In other words, Lowell believes that begging expresses ideas. Lowell simply wants to silence those ideas, which is exactly what governments must not do.

Content-based censorship is especially problematic when, as with begging laws, it is directed against the poor. They have the fewest options for expressing their views and face the greatest risk of having their expressions outlawed by those with more money or power. But this is wrong. As Judge Woodlock wrote, speech “cannot be burdened because it would discomfort comparatively more comfortable segments of society.”

That is correct. As Matthew Segal wrote in The Guardian:

It is now clearly established that the first amendment protects people who express themselves by spending millions of dollars. How can it fail to protect people who express themselves by asking for one dollar?

Lowell’s scorn can’t change the fact that poor people exist, that many of them have dire needs, and that they have the same free speech rights as everyone else. And Worcester, that goes for you, too.

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.