On Sunday, January 10, Rahsaan Hall, director of the ACLU of Massachusetts Racial Justice Program, delivered remarks for the 41st annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Celebration at Cambridge Public Library. Watch an excerpt from his talk, or read his remarks in full below.

As we gather here today to reflect on the life and work of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I am compelled to think about the current racial climate in this country. We are living in a time when the vitriolic rhetoric of political candidates is specifically targeted at stoking the fears and xenophobic anxieties of the “so-called” silent majority. We are living in a time where the pushback against tolerance, sensitivity, and inclusion is framed as political correctness fatigue. The reality is that certain folks are just tired of not being able to belittle and insult women, people of color and religious minorities. We are in a time when the response to the cry #BlackLivesMatter is “All Lives Matter” when in fact we know that all lives do not matter and have not mattered from this nation’s inception.

I find it disturbing when prominent Black leaders or celebrities are confronted with questions about the #BlackLivesMatter movement or any other organized effort of Black people to resist oppression, and they wade into the shallow pool of respectability politics. For example (disclaimer re: race and age) the RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan was recently interviewed and asked about #BlackLivesMatter and his response was one that I found deeply troubling and disturbing.

But before I tell you what he said I must first tell you who he is. Robert Diggs is known as the de facto leader of the group based in the New York boroughs of Staten Island and Brooklyn. The members of the group grew up witnessing the extreme poverty of their neighborhoods in juxtaposition to exorbitant wealth of Manhattan, they saw the violence in their community that grew out of the disenfranchisement and systemic oppression perpetrated upon them. They were also witness to the brutality of police misconduct and street level stop and frisk harassment. This was the context they grew up in. This was the world that shaped their perspectives and the music they would produce.

RZA, noted as one of the most prolific and influential producers in Hip Hop, lead the upstart group to the top of the charts time and time again with hits that changed the landscape of Hip Hop. As his stature and celebrity increased, he began to venture into other aspects of entertainment by starring in movies. He even tried his hand as an entrepreneur with the Wu-Wear clothing line. The influence of his music and celebrity are worldwide. He was recently interviewed for a Bloomberg news television series called “With all Due Respect.” When asked what he thinks about the #BlackLivesMatter movement he said, “Of course Black lives matter, all lives matter.” He talked about how the notion of all lives mattering influenced him to become vegan.

I can’t knock him for acknowledging that Black lives matter and being inspired to become a vegan out of a philosophical appreciation for the sanctity of all living creatures on the earth. But where he terribly misses the point is the historical context of racialized oppression and the systemic destruction of the Black body in this country. I think I would have been alright if he would have stopped there, but then he went on to suggest that young Black men are somehow responsible for their treatment at the hands of police. He stated that they need to “clean up their appearance” and “button their shirts.” As if to suggest that if Eric Garner, the man who was strangled by NYPD in Staten Island for selling loose cigarettes, would have been alive had he been wearing a suit.

Without fail, mainstream media will relentlessly seek out respectable Black spokespeople to discredit or chastise Black folks who are trying to get free. This is nothing new. In the late 1960s at the height of racial uprisings in major urban centers throughout the United States, Rev. Dr. King was asked what he thought about the “riots.” In 1966, for example, in a September 27 interview, Dr. King was questioned by CBS’ Mike Wallace about the “increasingly vocal minority” who disagreed with his devotion to nonviolence as a tactic. He said “I contend that the cry of ‘black power’ is, at bottom, a reaction to the reluctance of white power to make the kind of changes necessary to make justice a reality for the Negro,” He said, “I think that we’ve got to see that a riot is the language of the unheard. And, what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the economic plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years.”

Dr. King returned to that refrain again in March of 1968 in a speech entitled “The Other America.” He said, “But it is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society. These conditions are the things that cause individuals to feel that they have no other alternative than to engage in violent rebellions to get attention. And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear?...It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice and humanity."

The contingent, intolerable conditions that existed in our society at the time could be found in the Watts section of Los Angeles, California, for instance, in 1965. A community with a high concentration African Americans who began to arrive during the Great Migration in the early '20s when they were corralled into small segments of the city through the process of redlining and blockbusting. Other, more affluent sections of Los Angeles were effectively inaccessible to African Americans, and the communities like Watts suffered from financial deprivation and high unemployment rates, substandard housing, and inadequate schools. The racial harassment they experienced from marauding white gangs from neighboring white sections of the city as their numbers began to increase, continued into the '60s.

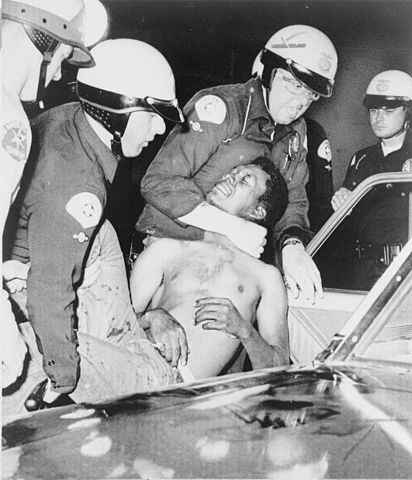

Police arrest a man during the Watts Riots. Image marked as August 12. World-Telegram photo by Ed Palumbo.

In addition to the crippling economic and educational disparities, being excluded from high paying jobs, affordable quality housing, and access to the political process, they were also subjected to abuses from the LAPD. Incidents of police harassment, misconduct and brutality were a regular occurrence, and on August 11 they pulled over 21-year-old Marquette Frye for suspicion of driving under the influence. The treatment that Frye, his brother and their mother—who arrived on the scene shortly after Frye was taken into custody—enraged the gathering crowd, especially when Frye’s mother was pushed by officers. What ensued was six days of the unheard making themselves known in the face of the police escalation and the military strength of the state of California.

The contingent, intolerable condition that existed in our society at the time could be found in Chicago, Illinois, for instance, in 1966. This community, in addition to the large population of African Americans who began to arrive during the Great Migration in the early '20s, had a large and growing population of Puerto Ricans. They were corralled into small segments of the city through the process of redlining and blockbusting. Other, more affluent sections of the city of Chicago were effectively inaccessible to African Americans and Latinos. They suffered from financial deprivation and high unemployment rates, substandard housing, and inadequate schools.

In addition to the crippling economic and educational disparities, being excluded from high paying jobs, affordable quality housing and access to the political process, they were also subjected to abuses from the Chicago Police Department. Incidents of police harassment, misconduct and brutality were a regular occurrence, and on June 12, a police officer was chasing 20-year-old Arcelis Cruz and his friend through an alley near Damen and Division Streets. The officer shot Cruz in the leg. This was witnessed by a group of people at the corner who attempted to come to Cruz’s aid. This enraged the gathering crowd. What ensued was three days of the unheard making themselves known in the face of the police escalation and violence.

The contingent, intolerable conditions that existed in our society at the time could be found in Newark, New Jersey, for instance, in 1967. This was a community that had a large population of African Americans who began to arrive during the Great Migration in the early '20s. They were corralled into small segments of the city through the process of redlining and blockbusting. Other, more affluent sections of the city of Newark were effectively inaccessible to African Americans. They suffered from financial deprivation and high unemployment rates, substandard housing, and inadequate schools.

In addition to the crippling economic and educational disparities, being excluded from high paying jobs, affordable quality housing, and access to the political process, they were also subjected to abuses from the Newark Police Department. Incidents of police harassment, misconduct and brutality were a regular occurrence, and on July 12 two Newark police officers pulled over John Weerd Smith, an African American cab driver, whom they alleged illegally passed them. Members of the community became enraged when they saw an incapacitated Smith being dragged into the police precinct. What ensued was six days of the unheard making themselves known in the face of the police escalation and the military strength of the state of New Jersey.

The contingent, intolerable conditions that existed in our society at the time could be found in Baltimore, Maryland for instance. This was a community that had a large population of African Americans who arrived during the Great Migration in the early '20s. They were corralled into small segments of the city through the process of redlining and blockbusting. Other, more affluent sections of the city of Baltimore were effectively inaccessible to African Americans. They suffered from financial deprivation and high unemployment rates, substandard housing, and inadequate schools.

In addition to the crippling economic and educational disparities, being excluded from high paying jobs, affordable quality housing, and access to the political process, they were also subjected to abuses from the Baltimore Police Department. Incidents of police harassment, misconduct and brutality were a regular occurrence, and on April 25 Baltimore residents gathered to protest the killing of Freddie Gray—who was arrested by police for fleeing the police. Once arrested he was transported in the back of a police van and suffered a life threatening injury to his spine. As a result of the injury and the lack of treatment, Freddie Gray died. What ensued was sixteen days of the unheard making themselves known in the face of the police escalation and the military strength of the state of Maryland.

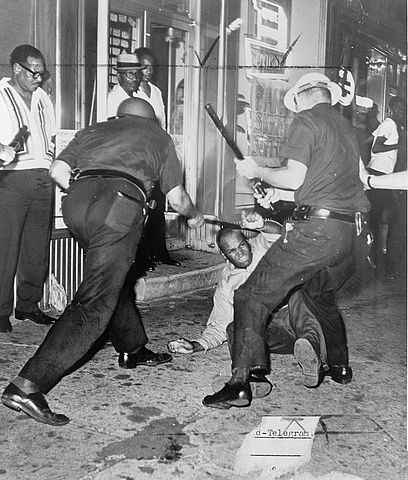

Incident at 133rd Street and Seventh Avenue during the Harlem Riots of 1964, photographed by a staff photographer of the New York World Telegraph & Sun.

This is not to be confused with the unheard making themselves known in Baltimore in the 1968 aftermath of the murder of Dr. King. Nor are any of these to be confused with any other uprising of oppressed people saying enough is enough. Notice the seamless transition between the incidents of roughly 50 years ago and the incidents of today. Since 1824, there have been documented accounts of violence erupting in this country because of race. Either people attempting to oppress and terrorize people of color, or people of color resisting oppression through conflict and struggle. That’s 191 years of civil unrest due to racial injustice. The greatest length of time without an incident was a nine-year stretch between 1876 and 1885. One hundred twenty-nine incidents over 191 years is roughly an incident every other year. Racial injustice has manifested almost every other year whether it was the Hard Scrabble race riots in Providence, Rhode Island in 1824, or the Detroit race riots of 1863, or the Atlanta race riots of 1906, or the Red Hot Summer of 1919, or the Tulsa race riots of 1921, or the Harlem riots of 1943, or the Cicero race riots in 1951, or the the Long Hot Summer of 1967, or Crown Heights riots of 1991, or the Oakland riots in 2009, or the Ferguson uprisings in 2014.

The conditions that precipitated these incidents grow out of a deep well of injustice that has plagued this nation since its inception. This country has wallowed in the original sin of slavery and has been trapped in a purgatory of unrepentant denial of accountability. The result of which is a country where life outcomes are statistically determined by race, and justice is not afforded to all. In his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” Dr. King wrote “Injustice anywhere is a threat justice everywhere.” Therefore, racial justice is a condition precedent for there to be justice for all. Racial justice is the elimination of structural and institutional barriers that impact life outcomes based on race and ensures life, health, and equity, regardless of race. Racial justice is the epitome of the beloved community.

So let us consider this notion of “Justice for All.” The most familiar source of this phrase comes from the Pledge of Allegiance. Something most, if not all, of us are very familiar with and can probably recite without giving it a second thought. But I doubt most of us know the origins of this pledge, the various iterations of this pledge, the dates when it was made a formal component of our compulsory education system, and what it intended to include.

The pledge first written by Francis Bellamy, a Baptist minister and self proclaimed Christian Socialist, who wrote a pledge that was to be quick and to the point to address what was perceived as the lull in patriotism and the growing lack of allegiance given the growing immigrant population. Bellamy’s pledge originally read, “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” It could have potentially included the words equality and fraternity. These words were important to Bellamy’s socialist values but given the concern over the demands for equality by women and African Americans at the time, the words were left out. The Pledge’s proclamation of justice for all without equality is indicative of this nation’s attitude towards African Americans and other people of color and our position of resistance throughout history. We have always been fighting and struggling to be included in the narrative of this nation’s history.

So what is justice without equality? It is the hollow promise of a morally bankrupt guarantor, it is the well plead complaint on a time-barred cause of action, it is the all-you-can-eat buffet with a tiny plate and a time limit. The fallacy of justice without equality provides a false sense of security in the era of an alleged post-racial society. A society where the grievances of #BlackLivesMatter activists, #ConcernedStudent1950, the Million Hoodie Movement, or any number of non-traditional grass roots movements in the black community are looked upon with disdain and disrespect, or dismissed because they are not respectful.

Justice without equality makes it okay for almost one fifth (19.4%) of all Black families in Massachusetts to be officially impoverished, and 28.2% of all Latino/a families to be impoverished. Compared to 4.8% for White families. Justice without equality makes it okay for Blacks and Latinos to have significantly higher unemployment rates than Whites, with the Black unemployment rate at 16.5%, and the Latino/a unemployment rate at 14.3%.

Justice without equality makes it okay for the homeownership rate for Blacks (32.7%) and Latino/as (25.1%) to remain significantly lower than the rate for Whites (69.5%). It makes it okay for Blacks and Latinos make up roughly 16% of the Massachusetts’ population, but make up 32% of those incarcerated, 43% of people convicted for drug offenses, and 75% of people convicted of drug offenses that carry a minimum mandatory sentence. This is particularly disturbing when the empirical data shows that Blacks and Latinos use drugs at relatively the same rate as Whites.

Justice without equality makes it okay for Black males between the ages of 15 - 19 to be killed by police at a rate of 31.17 per million, while Whites of the same age were killed by police at a rate of 1.47 per million between 2010 and 2012; or for 12-year-old Tamir Rice to be shot dead by police for playing in the park with a BB gun while armed White militias overtake federal property and be greeted with a handshake by the local sheriff.

We can no longer tolerate justice without equality. We can no longer condemn Black students at the University of Missouri whose protest forced the resignation of the University’s president, or the protesters in Chicago whose protests resulted in an estimated 25-50% loss of revenue on Black Friday. We cannot condemn them because, as Ida B. Wells said, “The appeal to the white man's pocket has ever been more effectual than all the appeals ever made to his conscience.” We can no longer condemn these actions without condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that precipitate them.

I am reminded of an Indian parable about a flock of Doves that was migrating and had become very hungry during their journey. The leader of the flock encouraged them to press on a little further so that they might find something to eat. A little while later they spotted some grains of rice and under a tree. The flock landed and while they ate, a heavy net fell on them ensnaring them so that they were unable to get free. As they struggled to get free they noticed a hunter approaching. The flock began to panic, but the leader told them she had a plan. She said, “if each of us grab a piece of the net and fly upwards we will be able to get away.” And so each of the birds grabbed a piece of the net in their beak and began to fly. The hunter noticed this and tried to pursue them, but they rose higher and higher until they got away from the hunter. Still constrained by the net, the leader told the flock to fly to see a nearby mouse who would be able to free them. The leader told the mouse the story and instead of asking the mouse to free her she ensured that the rest of the flock was freed first, and so the mouse began to nibble away at the net eventually freeing all of the Doves.

I think about how the uncomfortable political climate, the gross racialized disparities and the corporatized exploitation of the poor have us as a nation ensnared and doomed for a fate at the hands of the hunter. Racial justice is the intentional effort of each of us individually taking our piece of the problem and collectively flying to safety. We must recognize, as Dr. King wrote in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, that in addition to “injustice anywhere being a threat to justice everywhere...” that “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality tied in a single garment of destiny.”

So we must advocate, join organizations, not be silent, educate ourselves, endeavor to put ourselves in situations where we are learning from others not like us, call elected officials, march, protest and resist!

We cannot be satisfied with freeing ourselves, we must ensure that we all get free! We must recognize that our destiny as a nation and as individual are linked together and therefore racial justice is justice for all!