To fix racial disparities, legislators must repeal mandatory minimums and address race

The racial disparities in the Massachusetts criminal justice system are worse than the national trend, but it doesn't have to stay that way. Massachusetts legislators have a unique opportunity to enact significant criminal justice reform by addressing racial disparities. The Counsel of State Governments recently released its justice reinvestment policy report for Massachusetts. The report included suggestions to decrease the rate of recidivism by investing in programing, reentry reform and addressing behavioral health needs. The report also makes a recommendation to improve the data collection and reporting related to race and ethnicity.

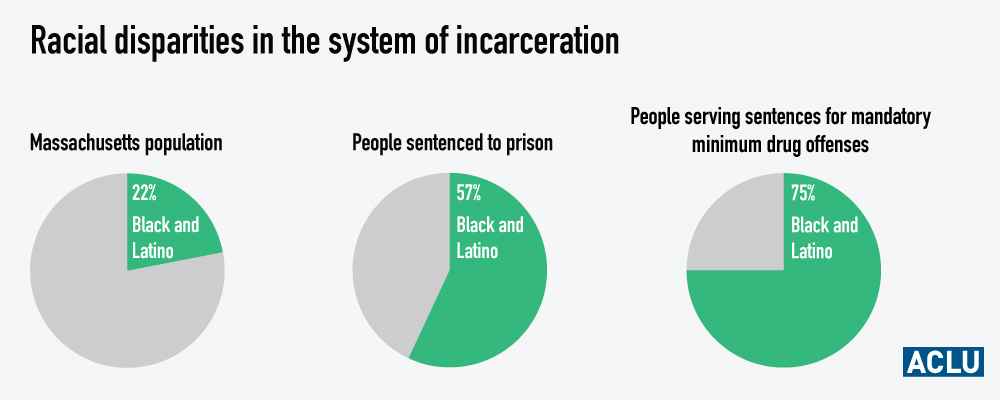

Black and Latino residents make up roughly 22% of Massachusetts population, 57% of those sentenced to prison and 75% of people serving sentences for mandatory minimum drug offenses. Black people in Massachusetts are incarcerated at nearly eight times the rate of whites, which is higher than the national incarceration rate disparity of six to one. Similarly, Latinx people in Massachusetts are incarcerated at five times the rate of whites. This particular disparity is nearly four times the national disparity, which is close to equal (1.3:1). With disparities like these it would make sense for legislators to be eager to take bold steps to reform the criminal justice system in the Commonwealth.

Unfortunately, the justice reinvestment policy report and the accompanying legislation come nowhere close to addressing these gross racial disparities or engaging in meaningful reform. Improving the collection of race and ethnicity data is a step in the right direction. The problem is that this recommendation – as well as many others – was not included in the justice reinvestment bill filed by Governor Baker. The bill was the culmination of a months-long data driven analysis of Massachusetts' criminal justice system for the purpose of identifying policy opportunities to reduce recidivism and create savings.

As a result, criminal justice advocates are disappointed that comprehensive reform efforts were not included in the justice reinvestment policy report or the accompanying legislation. Requests for the repeal of mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses, diversion to treatment, bail reform, or any other measure targeted at reducing the overall number of individuals entering the system to begin with, were left unanswered. Although the governor included $3.5 million for justice reinvestment as a budget line item, the overwhelming number of recommendations from the policy report will require executive and administrative action as well as continued budgetary commitment over the next six years to come to fruition.

Instead of one comprehensive omnibus reform bill there are dozens of free standing bills filed separately by different legislators that address various aspects for the criminal justice system. Reform advocates are now left to coordinate their efforts to identify the most viable set of bills to create true reform. The danger with the justice reinvestment process not being comprehensive is that legislators and law enforcement officials run the risk of patting themselves on the back for investing in efforts to reduce recidivism while totally ignoring the opportunity to bring the incarceration rate in line with the rest of the industrialized world and significantly reduce racial disparities. There's a concern among advocates that they legislature won't take on enough of the freestanding bills to significantly reform the Massachusetts' criminal justice system.

From the outset of this justice reinvestment journey, elected officials have been somewhat reluctant to embrace the challenges of criminal justice reform. Pointing out that Massachusetts has the second lowest incarceration rate in the United States, they have conveniently overlooked the fact that our incarceration rates outpace most of the industrialized world. Moreover, they are reluctant to address the racial disparities except to say they don't understand the cause of the disparities. Several district attorneys have even absolved themselves of responsibility and suggested that the criminal justice system is the dumping ground of society and they have no role in the maintenance of racial disparities, nor do they contribute to them.

With that type of perspective any reduction in recidivism may be at the expense of eliminating or significantly reducing racial disparities. There is ample evidence about the disparities within the criminal justice system from police encounters and arrests, bail, and who has access to diversion programs, charging and sentencing decision, probation and parole rates and the locations where incarcerated individuals are coming from and returning to. After years of advocacy for reform and months of waiting for criminal justice data, advocates fear the legislature will only tinker around the edges of the back-end of the system and leave for another day the question of race and its role in the criminal justice system.

Advocates will continue to demand meaningful reform just as we always have, but we will rededicate our efforts to ensuring the legislature and law enforcement officials do more than just reduce recidivism. We cannot let this opportunity to do justice pass without addressing the serious racial disparities that plague the system.

Tell your state legislators: We need a broad array of reforms to fix our broken justice system—including repeal of mandatory minimum drug sentences.

Rahsaan Hall is the director of the Racial Justice Program at the ACLU of Massachusetts.

Related content

Federal Court Grants Preliminary Injunction Against Department of...

April 24, 2025Researchers Challenge NIH’s Politically Driven Grant Cancellations

April 2, 2025ACLU and NEA Sue U.S. Department of Education Over Unlawful Attack...

March 5, 2025

ACLU of Massachusetts statement on recommendations to reinforce...

October 16, 2024

ACLU of Massachusetts responds to Supreme Court decision in Grants...

June 28, 2024

Massachusetts for Overdose Prevention Centers comment on new VT law...

June 18, 2024

Juneteenth 2024: Celebrating the Past and Redefining the Future of...

June 13, 2024