A movement 50 years in the making

You can kill a person, but you cannot kill a movement.

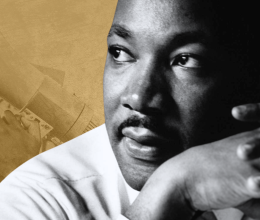

Reflecting on the 50 years that have passed since the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated, nothing can accurately – and fully – describe the impact that he had on the trajectory of this nation’s history.

Despite his profound legacy, we find the liberal multitudes of this nation recoiling in abhorrence to the wayward journey we as a nation appear to be on. It feels like our country is traversing the long moral arch of the universe and coming no closer to any semblance of justice. For many, this is a shocking and recent revelation, but others recognize we are on a well-worn course plotted long before November 2016.

The legacy and unfinished work of Dr. King are stark reminders of our failings to recognize the full humanity of all who dwell among these shores. His fight for equality and liberty grew out of a century-old struggle for true emancipation and citizenship. Recognizing that racial justice is justice for all, Dr. King remarked on the night before he was killed that some of the white people present that evening had “come to realize that their destiny is tied up with [Black people’s] destiny and their freedom is inextricably bound to [Black people’s] freedom.” But the inability of some – and outright refusal of others – to recognize the humanity of Black people led him to engage in an advocacy that went beyond civil rights.

His advocacy was one that is yet to be fully embraced presently. The persistent racial disparities that exist between Blacks and whites in many instances are the same as – and in some cases, worse than – those 50 years ago. Despite having higher rates of graduation than in years past, the Black unemployment rate in 2017 was 7.5 percent – up from 6.7 percent in 1968 – and still roughly twice the white unemployment rate. Rates of incarceration for Black people have nearly tripled from 1968 to 2016; then, it was 604 of every 100,000 in the total population and in 2016, 1,730 per 100,000.

While Dr. King’s name is known and revered for his fight against segregation and voter discrimination, his final campaign is lesser-known. He took that fateful trip to Memphis to elevate the need for Black people’s humanity to be recognized by ensuring economic rights. Called the Poor People’s Campaign, the later years of Dr. King’s life and advocacy found him organizing with others to develop a movement for economic justice. From living wages for sanitation workers in Memphis to an investment in basic human needs, Dr. King and others developed a platform with unprecedented demands: an Economic Bill of Rights for America’s poorest people, a $30 billion annual appropriation to fight against poverty, guaranteed income legislation, and the construction of 500,000 low-cost housing units each year until slums were eliminated.

Although the vision of the Poor People’s Campaign never fully came to fruition, the need for a movement that advocates for and protects the basic dignities entitled to all people is more relevant today than ever.

That’s where the ACLU strives to be: in the midst of the movement to protect basic human dignities. We’ve been in the courts fighting to defend and protect the oppressed and least among us. Look at our work in Moe v. Secretary of Administration and Finance, which required legislators to secure reproductive rights through the Commonwealth budget so those rights are equally enjoyed by all and not just the wealthy – or take Thayer v. City of Worcester, which ensured the First Amendment right to publicly solicit donations is not infringed upon merely because one is poor.

Injustice, oppression, and white supremacy abound, challenging the ideals of this democracy and threatening the lives of the people. But we continue to stand with the masses of people who have risen up, marched, protested, and advocated in a manner reminiscent of the era Dr. King personified.

Fifty years later, there is a movement afoot and it cannot be killed.

Rahsaan Hall is the director of the Racial Justice Program at the ACLU of Massachusetts.

Related content

Federal Court Grants Preliminary Injunction Against Department of...

April 24, 2025Researchers Challenge NIH’s Politically Driven Grant Cancellations

April 2, 2025ACLU and NEA Sue U.S. Department of Education Over Unlawful Attack...

March 5, 2025

ACLU of Massachusetts statement on recommendations to reinforce...

October 16, 2024

Juneteenth 2024: Celebrating the Past and Redefining the Future of...

June 13, 2024

Black History Month

February 1, 2024

Finding the courage to be change-makers in our communities

January 11, 2024